In 2013, conflict broke out in South Sudan. A hopeful country—one that won its independence just two years earlier, on July 9, 2011—found itself imploding. To date, the vicious and bloody civil war between government and opposition forces is believed to have claimed at least 50,000 lives, driven 2 million people out of the country and displaced as many inside South Sudan.

A UN peacekeeping mission, UNMISS, has been stationed in the country since 2011. The mission—17,000 soldiers strong—has been given the difficult task of ensuring peace and security in a conflict infamous for its indiscriminate attacks on civilians, high prevalence of sexual violence and use of child soldiers.

But this story is not about the immediate and ruthless damages inflicted by war. This story is about the subsequent struggle—about what happens to the mind when a person has found shelter and is assumed to be out of danger. Driven from your home, having witnessed or fallen victim to atrocious acts—what happens once you reach safety? What happens to the agony and the invisible, mental wounds inflicted by brutal conflict?

28-year old Chan is sadly very familiar with the mental perils of conflict. Originally from South Sudan’s Upper Nile region, Chan was living a good life before the war: he excelled in basketball at school and was a well-known artist in his hometown.

Chan is one of the millions of people who have been forced from their homes because of the conflict. Today, he and his wife live in a Protection of Civilians (PoC) site in South Sudan’s capital Juba. Together, the Juba PoC sites host close to 40,000 civilians seeking safety from the war and its menaces. Across the country, a total of 200,000 civilians are temporarily sheltered in UNMISS PoC sites across the country.

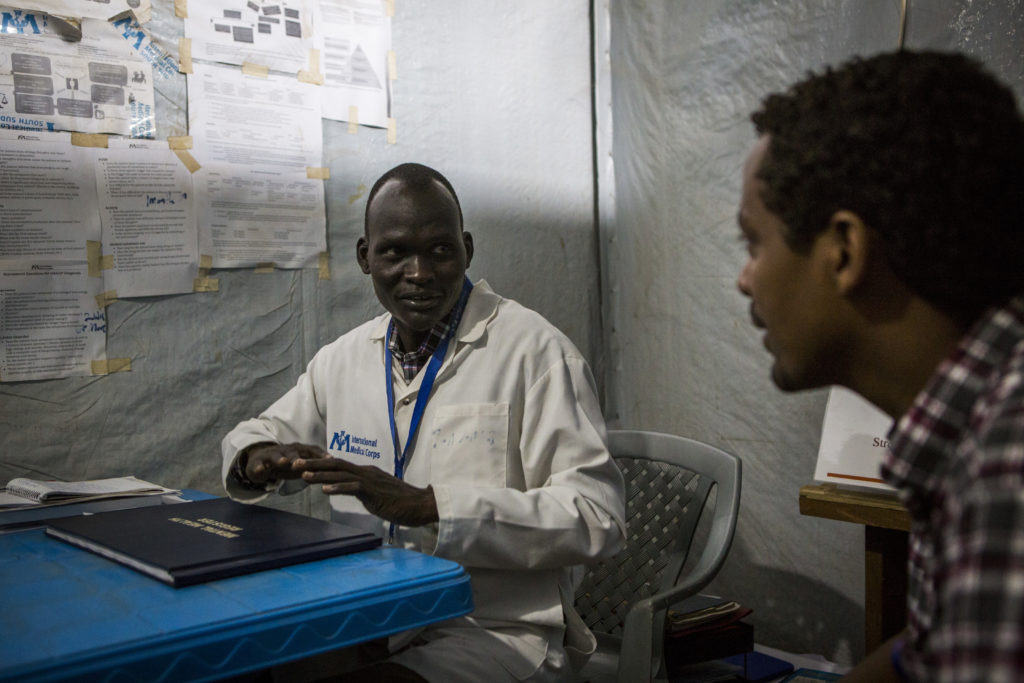

As the main healthcare provider inside the PoCs, International Medical Corps runs the camp clinics. Our country-team also operates a comprehensive mental health and psychosocial support (MHPSS) program that offers counseling and treatment, as well as psychosocial support activities and awareness-raising activities.

The war had only just erupted when Chan’s family noticed that something was wrong. The 28-year old’s behavior was changing rapidly: Chan started to struggle with his appearance and he became aggressive. Verbally, Chan grew increasingly more difficult to understand, with words and sentences no one could make sense of—much like his deeply disorganized behavior overall.

Before Chan met International Medical Corps’ MHPSS team, he was kept in a UNMISS holding facility. For more than a month, he had been a danger to himself and others, and as a result was kept detained. Looking back at the situation today, Chan remembers how this left him feeling helpless:

“Things were not easy; people thought I was very dangerous. I lost hope, thinking life had no purpose anymore—everything just seemed to be going wrong.”

Deeply concerned about his well-being, Chan’s family put him in touch with International Medical Corps’ MHPSS-team in the PoC. When discussing it today, Chan’s family says:

“We didn’t know what was happening to our brother.”

Once at the health facility, a clinician diagnosed Chan with psychosis and prescribed him with antipsychotic medicine. Over the following weeks, International Medical Corps’ psychosocial staff worked closely with Chan and his family to assess his progress and address any external factors that were triggering his psychosis. The staff also worked to help prevent the discrimination and stigma that Chan was often exposed to because of his disease.

After several weeks, Chan’s condition improved significantly: his dysfunctional and sometimes-bizarre behavior had calmed enough that he was able to carry out household chores. Today, Chan is back to his normal self. Speaking to International Medical Corps’ team in Juba, he says:

“I am happy. I never thought I would get married but now I am—I’m able to take care of myself and my wife.”

Grateful that her loved one has recovered, Chan’s family member Nhial says:

“I am happy Chan recovered from this ‘sickness of the brain.’ Now, we advise people with similar conditions to seek treatment and remain committed to medication.”

Because Chan and his family were brave enough to seek help rather than suffer in silence, other people whose mental well-being has taken a toll because of the conflict are now able to learn about the MHPSS services that International Medical Corps provides in the camp. We can only hope that as the road to recovery for Chan continues, the road to peace for South Sudan does the same.