When Zahra’s family heard Islamic State ISIL forces had captured the nearby northern Iraqi town of Sinjar in the summer of 2014, they fled their home with just the clothes on their backs. Like tens of thousands of other members of an ethno-religious minority known as Yazidis, they set off on foot to seek refuge in the mountains not far away, their children in their arms and Zahra pregnant with their seventh child.

“ISIL saw us and shot at us, but we kept moving,” Zahra recalls, referring to the terrorist group Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant, which views Yazidis as heretics, who should be killed.

They walked for eight days straight with barely any food or water until they reached the top of Mount Sinjar, where they stayed briefly before pressing on to the relative safety of Iraq’s Kurdistan Region. A year and half later, the family of nine now lives alongside other Yazidis in an unfinished concrete building in Siji, a village of roughly 8,000 people perched on a hillside. It was here that Zahra and three of her children started to see mysterious, painful sores emerge on their hands.

“After just 10 days living here we started to see small spots on our hands,” Zahra says. “I didn’t know what it was until the community health worker came.”

Like them, the community health worker (CHW), Jalal, had settled in Siji after being forced from his home by the ISIL attack on Sinjar. He is one of four CHWs that International Medical Corps recruited and trained in Siji to educate families like Zahra’s about common health issues, including a flesh parasite that causes skin ulcers known as leishmaniasis.

The parasite that produces leishmaniasis is spread through the bites of sandflies. The kind commonly found in Iraq, known locally as the “Baghdad boil,” is cutaneous leishmaniasis, which creates skin ulcers that can leave lifetime scars. There are as many as 1.3 million cases reported annually around the world, according to the World Health Organization, and is commonly found in displacement crises among those who live in close proximity to one another in poor housing conditions.

Siji is no exception.

Most of the people who live in Siji are Yazidi, like Zahra, a minority that makes up just 1.5 percent of Iraq’s 33 million people. Thousands of Yazidis were slaughtered and kidnapped by ISIL (also known as ISIS) when they attacked Sinjar on August 3, 2014. Others died later after they were trapped on Mount Sinjar with little food or water. Those who survived are now displaced from their homes and many of them have sought refuge in camps and unfinished buildings like those in Siji.

“At the beginning there was no pain, no itching, but then it became inflamed,” says Zahra, “It affected me a lot. I couldn’t cook or clean. The pain was really bad.”

When International Medical Corps set up a mobile medical unit (MMU) in Siji roughly one year ago, leishmaniasis was one of the most common health issues people sought care for. “We have seen at least 60 cases of leishmaniasis since we started working here,” says Dr. Moamer Abdulghafordr Agha. “We are seeing less and less. In March, we saw just four cases.”

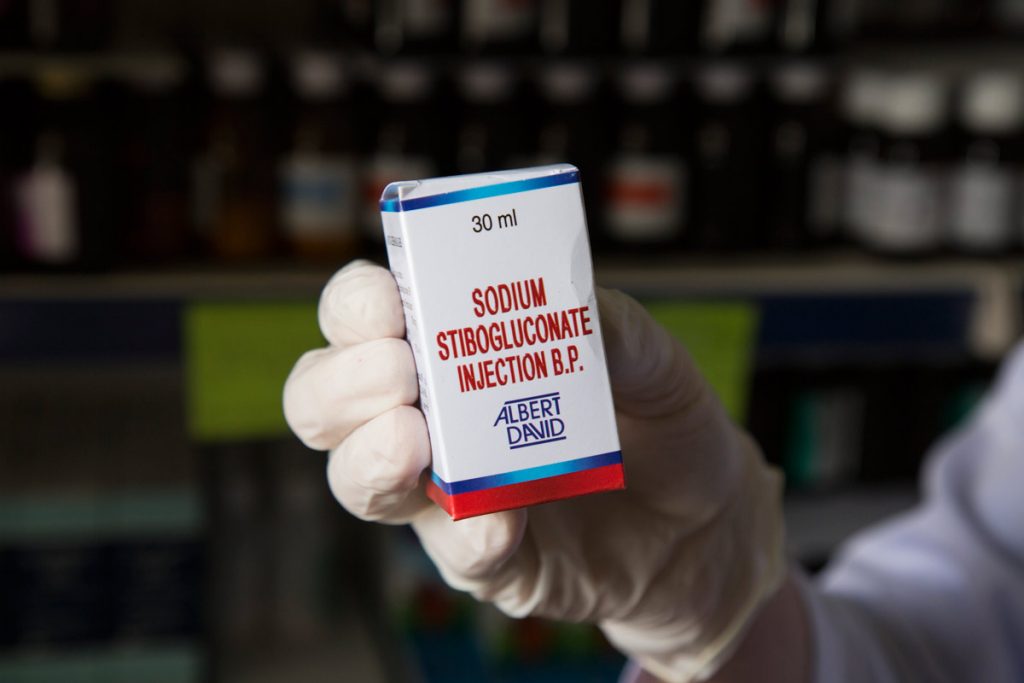

The main reason for the decline, Dr. Moamar says, is improved access to treatment through the MMU. At first, the MMU would have to refer people to a government hospital about 30 minutes away to get the injectable medicine that is the most effective remedy for leishmaniasis. The treatment also requires multiple follow up visits, which meant families had to travel back and forth from the hospital a number of times before they were cured. As soon as International Medical Corps had a steady supply of the drug, they could administer it at the MMU, making it much more easily available to the Yazidi families living in Siji.

When the injectable medicine arrived, Jalal visited Zahra and suggested that she and her three children, all of whom had sores, visit the MMU. “After a week it started to go away,” she says. “It is cured now.”

Not all cases of leishmaniasis are so easily cured. For 15-year-old Basi Hassan Ibrahim, the sore appeared in the corner of her left eye. The area is too risky to use the injectable drug, so she uses a topical medicine, which is much slower to take effect. “I am afraid [the sore] will affected my eye,” says Basi, who is one of five members of her family to get leishmaniasis.

Like Zahra, Basi’s family fled Sinjar and resettled in an unfinished concrete building in Siji. They also did not know what the sores were until a CHW diagnosed the issue and explained it to them during a visit. “The CHW came and told us we had leishmaniasis,” says Basi’s mother Shereen. “They told us to go to the clinic.”

“The CHWs are the link between families and our clinics,” says Alexander Bartoloni, Regional Community Health Advisor for International Medical Corps. “They are a part of the communities themselves and are able to improve health on a grassroots level by going door-to-door and talking to people about any health issues affecting them. They also look out for symptoms of common diseases, like leishmaniasis, and connect the family with our doctors and nurses who can then treat it.”

While leishmaniasis cases have declined in Siji, Jalal and his CHW colleagues walk up and down the hillsides of Siji, meeting with families and connecting them to the MMU down the hill. “They visit us all the time,” says Shereen. “They give us advice about our health and hygiene. If we have a problem, they refer us to the clinic. They help us a lot.”

Shereen’s husband now has a sore on his leg, but is resistant to go to the doctor. The CHWs are encouraging him to seek treatment, while checking on Basi’s progress regularly. Outside, Basi’s younger sisters played on a grassy knoll, their foreheads and cheeks pock-marked with circular scars, reminders of the boils they had months earlier.