It’s been two years since the devastating port explosion ripped through Beirut city on August 4, 2020—damaging infrastructure, injuring more than 7,000, displacing around 300,000 and shattering many more dreams and hopes. Members of the community have since worked to pick up pieces of their lives and tried to rebuild and restore their homes and their city. But the wounds from that fateful day—both visible and invisible—continue to haunt people.

Daoud Ayyash, a university student who will soon graduate, was about 20 kilometers away from the explosion’s epicenter. He and his family were physically safe, but the psychological stress that they went through manifests in normal everyday settings, even today. “The slightest of sounds, like a door slamming shut or a car being hit, triggers the feeling of another disaster,” he said. “For people who were closer to the blast area, or who lost their loved ones—I don’t think their pain will fade away quickly.”

When the blast occurred, Lebanon already had been reeling under an economic crisis and the COVID-19 pandemic. Due to the civil war in neighboring Syria, the country hosts the highest per-capita number of Syrian refugees globally, and the fight for limited resources is an ongoing battle. According to a UNICEF report, close to 75% of the Lebanese population—including migrants and refugees—live in poverty. For a country that was already under stress, the Beirut blast was the tipping point.

Affordable healthcare is a dream for many

The explosion hit the public health infrastructure hard. It destroyed many hospitals and health centers, and contributed to a disruption in access to medicines and medical supplies. A policy brief by the UN Economic and Social Commission for Western Asia states that the share of households deprived in healthcare increased from 9% in 2019 to 33% in 2021, while the share of families who were unable to obtain medicines increased by more than half. This means that some patients had to decrease the dosage of medicines they were taking, while some had to stop their medication completely. Some are also skipping their routine medical check-ups, explains Jad Salameh, International Medical Corps’ Chief Pharmacist in Lebanon.

“Today, healthcare has become a luxury for the masses,” Salameh says. “The low purchasing power of the people prevents them from accessing pharmacies, clinics, laboratories and hospitals. Before the economic crisis started, people relied on the National Social Security Fund (NSSF) to reimburse healthcare expenses, but now the NSSF is unable to do so, and for majority of the patients, the private insurance fee is quite high.”

Another factor that has resulted in the shortage of medicines and medical supplies is the country’s subsidization policy. Though the government began subsidizing medical products soon after the economic crisis started in 2019, there began to be a gradual shortage of medicines in the market. “When you subsidize anything, its risk of abuse increases,” explains Salameh. “Due to the uncertain economic situation, people have been stocking up on quantities or have been using products irrationally. So, if a patient stocked up on a month’s supply of chronic medication [before the shortage], looking at the uncertainties now, the patient would stock up for six months.” And it’s not just patients—vendors and pharmacies began buying extra supplies of medications and medical supplies, too.

The government has since ceased the subsidies, which has eased shortages. However, the country’s economic problems—including high rates of inflation—have meant that medicines can be prohibitively expensive.

Though some poorer patients have had to stop their medications at the risk of their lives, a handful of individuals who are better off financially are purchasing medicines from abroad. “You can see many passengers coming out of the Beirut airport with an extra piece of luggage filled with just medicine boxes,” says Salameh. “This is a dangerous trend, and opens the door to counterfeit medicines entering the country.”

Access to affordable medicine is just one challenge facing Lebanon’s healthcare system, which is also faced with rising costs, staff shortages and increasing demand from a patient base that has more medical needs than before—and less ability to pay.

All of this adds to the psychological distress of the people, many of whom started suffering from mental health conditions such as anxiety and depression after the blast. Just as it’s made medical care more expensive, the economic situation in Lebanon has made mental health care more expensive, according to Ayyash. “Anyone who could pay for these services earlier can no longer afford to do so.”

Giving hope with free medicines and counseling

In response, International Medical Corps has been working closely with the Ministry of Public Health (MoPH) to ensure that patients have access to lifesaving medical care. “In collaboration with International Medical Corps, the MoPH provides healthcare services bundles, in which medications are an essential item,” says Dr. Randa Hamadeh, Primary Healthcare Clinics Unit Director at the MoPH.

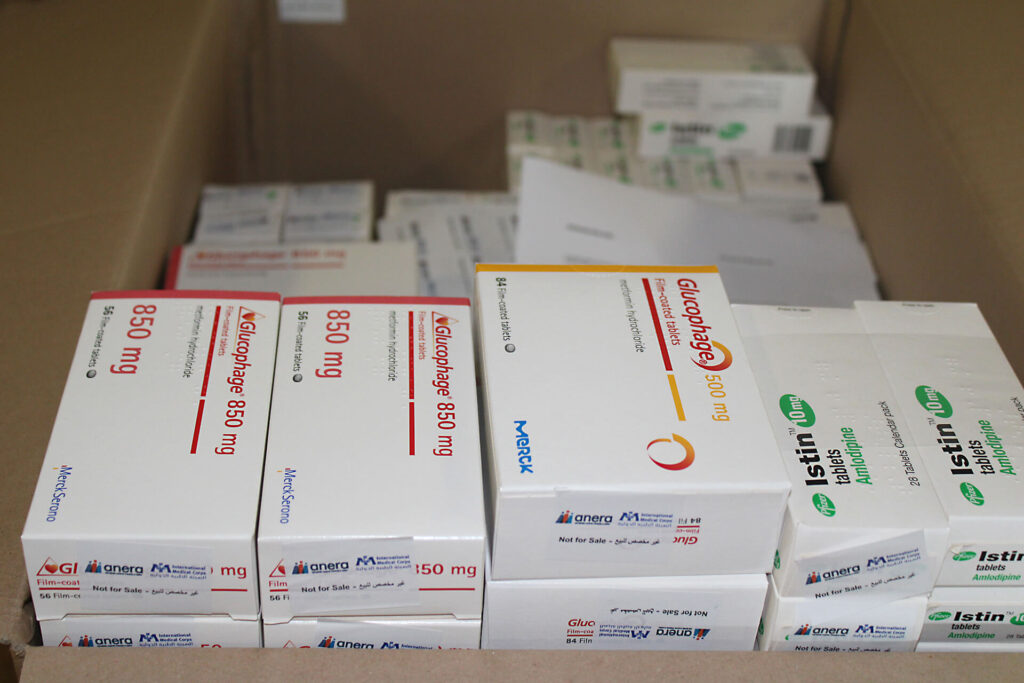

International Medical Corps procures medicines from local and international vendors, and since the beginning of the economic crisis has taken measures to expand our network of vendors. “Our strategy is to locally source what is available at acceptable prices,” Salameh says. “Whatever is not available locally or is expensive, we import internationally from humanitarian procurement centers, such as Imres and the International Dispensary Association Foundation.” This year, we have procured 10 batches of medicines so far, and distributed nine.

International Medical Corps supports 57 primary healthcare centers (PHCCs) across Lebanon, where patients can receive subsidized consultations and diagnostic tests approved by our medical advisors, and free medicine. All medications are subject to international standards and pharmacists’ supervision. “Our team of experts visits the PHCCs and teach the staff how to correctly store and dispense the medicines. Our pharmacists have an advisory and monitoring role to play,” adds Salameh.

Since August 2020, we have provided 105,000 patients with medication. But medicine is just one of the ways that we support PHCCs in Lebanon. Since the blast, we have provided more than 117,000 mental health consultations to people at the PHCCs where we operate, as well as 72,000 antenatal consultations, 7,000 postnatal consultations and 190,000 diagnostic tests.

For a university student like Daoud Ayyash, receiving mental health services from International Medical Corps has been both beneficial and encouraging. “The therapy sessions boosted my self-confidence, and helped me to love and accept myself. There’s nothing wrong in seeking professional help from organizations like International Medical Corps that provide counseling services for free.”