Even before the World Health Organization (WHO) declared COVID-19 a global pandemic on March 11, International Medical Corps had been assisting Libya’s National Center for Disease Control (NCDC) to fill gaps in its capacity. Among those gaps was the agency’s inexperience in responding to a major healthcare crisis, especially one involving new and emerging infectious diseases.

Although Libyan authorities had already created several locally based rapid response teams (RRTs) to face such a disaster, the teams had received little or no recent training. Given that training is a core strength of International Medical Corps, the two organizations quickly decided to put together a course focused on COVID-19. Since then, International Medical Corps has begun providing training to health workers serving on those teams that operate in large municipalities, such as Tripoli, as well as in smaller towns in more remote areas, including Sabha and Albawanis to the south, and Nalut and Zintan in the Nafusa Mountains to the east of the capital.

Each RRT includes four or five skilled health workers, including a physician, a surveillance officer, a medical technician, a data entry officer and, in some cases, an epidemiologist.

“So far, we have trained nearly 20 of these teams plus our own staff,” notes Muhanned Elshames, a physician and one of five medical coordinators on the International Medical Corps staff based in Tripoli.

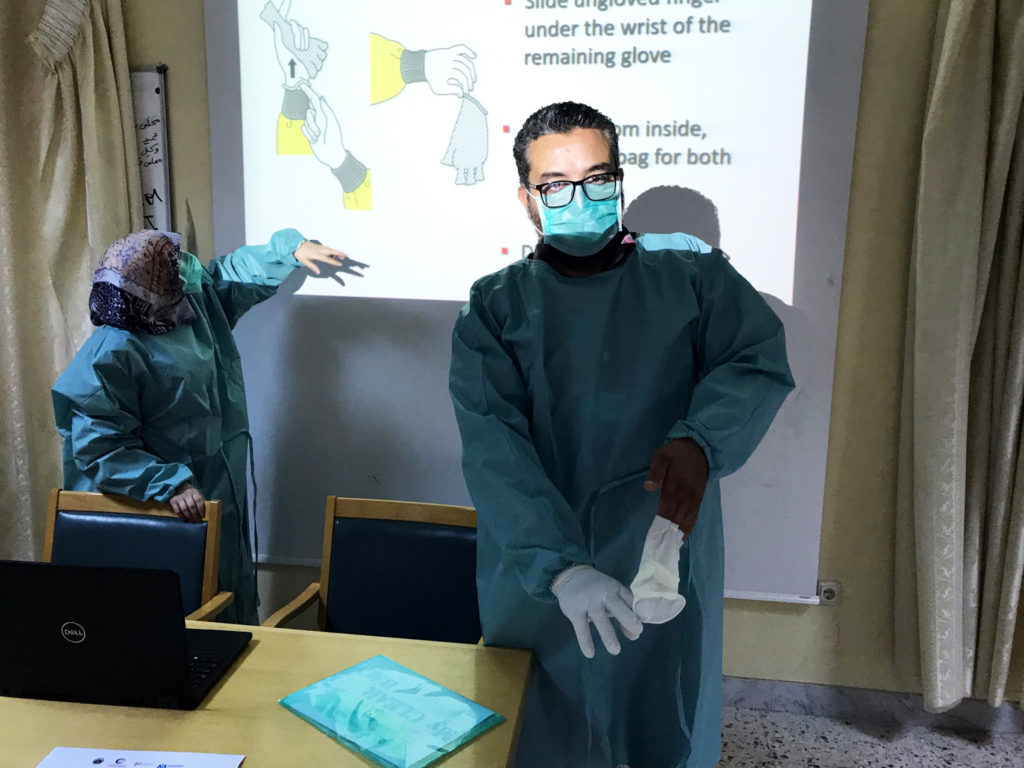

“Using updated WHO-approved procedures, we focus on triaging possible COVID-19 patients, as well as how to approach a case and how to use personal protective equipment (PPE) to keep them and others safe. We also train them on how to collect samples, then how to transport them to Libya’s only reference laboratory equipped to identify the coronavirus. Located in Tripoli, the lab uses the internationally approved technology known as polymerase chain reaction—PCR—that magnifies the virus’s genetic material if it is present.”

To strengthen the capacity of the RRTs, International Medical Corps has also trained and equipped four physicians and a nurse for an additional response team that will be based at the NCDC in Tripoli. Despite these achievements, however, resources to support these teams remain a significant challenge. For example, though some response teams have an ambulance to transport patients to health facilities for triage and possible treatment, others must rely on their own privately owned vehicles.

“There has been some improvement,” Elshames says, noting that the NCDC has provided access to appropriate transportation to more—but not all—response teams. “They still lack the resources they need. Even so, we’re hoping support from the government will grow.”

He notes that one of the biggest challenges International Medical Corps faces in strengthening Libya’s response to COVID-19 is finding adequate supplies of good-quality PPE for the Libyan RRTs we support as well as our own staff.

“In the local markets, the quality has been so poor that we’ve had to return much of what we’ve purchased, while the prices are now very high,” he explains. “An N95 mask worn by a health worker dealing with a suspected case cost $2 a few months ago. Today, we have to pay $15 to $20 for that same mask.”

Because the pandemic has forced the closure of many government and privately-owned health facilities in Libya that normally treat those struggling with chronic but non-communicable conditions such as diabetes, asthma or hypertension, International Medical Corps has worked to fill that gap by setting aside space for such patients in primary healthcare clinics it supports. Still, even here our staff must carry their PPE with them in case a suspected COVID-19 case should walk in.