March 21, 2017 – Blog Entry #6

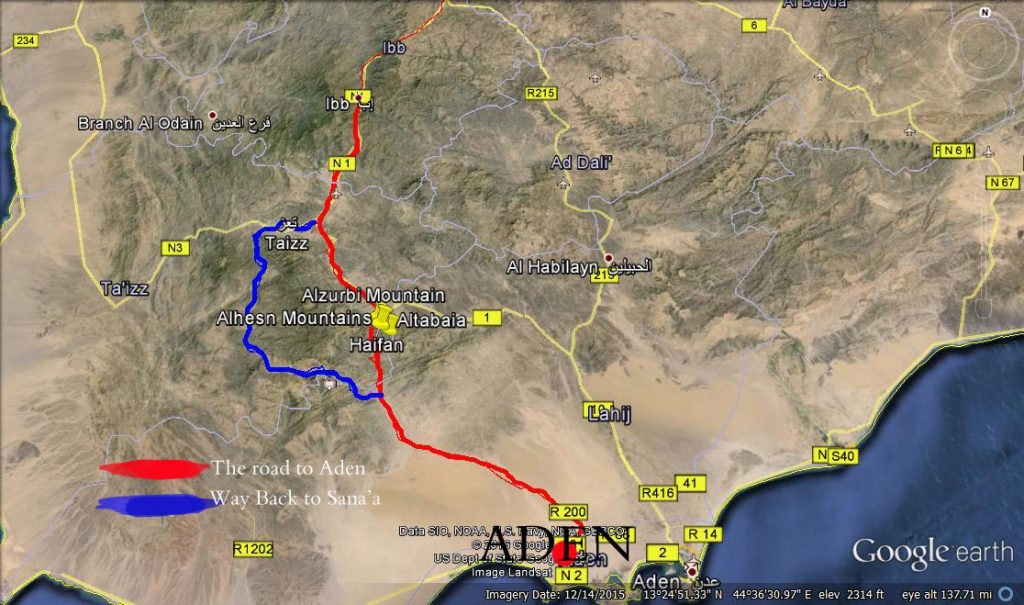

Editor’s note: In the month that marks the the second anniversary of Yemen’s seemingly directionless civil war, Yemen Country Director Giorgio Trombatore recently completed a roundtrip by road from International Medical Corps’ main office in the capital, Sana’a, across the front lines that separates the warring factions, to visit our office in the southern port city of Aden. Along the way, he chronicled the toll that prolonged armed conflict has exacted on a people whose country was already the Middle East’s poorest when the fighting began in March of 2015. Below is the account of his return journey from Aden to Sana’a.

It is 5 o’clock on a March morning.

My Team is gathered, preparing to leave Aden for Sana’a. It’s a distance of about 250 miles that takes us across the front lines of Yemen’s nearly two-year-old civil war and we intend to do the 13-hour journey in one shot with a few planned stops. Prior to leaving, we carry out routine checks on the vehicles, the travel permits, and water. Everything seems all right. I signal my security officers a thumbs-up and the team quickly moves to their vehicles. We have a small convoy this time—just four vehicles. As I get in, I try to get as conformable as possible in order to enjoy the trip. Aden at this early hour is captivating: The Gulf of Aden shoreline that carries the faded beauty of the city’s colonial era. A hilltop church that still stands strangely intact, now used as a museum and for art shows. Aden’s main hotels showing the scars of fighting, stand half destroyed and vandalized. We pass by Krater and I can see the fish market near Sira Qala stirring despite the hour. Fishermen nearby are already aboard their boats as hungry cats gather around young Yemeni men preparing for their business day. At this early hour, Aden is at its most enjoyable: the streets are empty, the air cool and fresh. The Minarets’ call and the solitude and the empty roads are like scenes from the early 20th Century British writer, Peter Hopkirk, whose rich characters and exotic settings served as the backdrop for the intrigues of The Great Game played out along the Asian cusps of the British and Russian Empires in the 19th and early 20th Centuries.

As we leave Aden not all those manning the check-points along the way are ready. Some don’t even bother to raise their head as they sit cross-legged around a big bowl of food, sharing breakfast. We use the food distraction to our advantage—moving quickly to get out of the city as soon as possible as we head north toward Sana’a. As we drive we pass by villages where International Medical Corps community health workers are deeply engaged in a hygiene promotion campaign.

After a few hours, we arrive in Naqil Al Khashabah, on the other side Yemen’s political divide. Land governed by the internationally-recognized government based in Aden is behind us now. We are back in Houthi-controlled territory. As we take a moment to drink tea and try to find a cosy place for a “toilet” I can see that the ground is littered with 12.7 x 108 mm shell casings from a Soviet heavy machine gun.

Two years of war has left this section of the main road largely unchanged. It is my sixth trip traveling between Yemen’s capital city, Sana’a, and the country’s main port of Aden and all the towns and villages along the way now seem familiar. There are also some permanent fixtures—like the plastic bags that gather by the thousands along the roadside, or the young soldiers at the check-points who keep on chewing Qat, the ubiquitous shrub leaf, to get a mild high. Both are always here. Omnipresent. Young soldiers, some with a striking beauty, a wild look, uncontrolled thick curly hair and a “Mahwuas Dress” wrapped around their skinny bodies, are also part of the panorama landscape, present around the check-point area. Sprawled on the ground, they listen to the melody of a popular Bedouin Yemeni music group called the “Zamil” whom Yemenis from both north and south love. The music is catchy and sometimes I even ask my driver to play it. It’s also filled with an energy that has not gone unnoticed by propagandists on both sides who have used it to accompany video footage from the war.

Just under half way to Sana’a we reach Ibb, one of the most peaceful and untouched towns of the entire country, where the situation is completely different.

The roads are as usual packed with noisy vehicles. People are everywhere on busy streets. Traffic jams are common. At International Medical Corps, we try to cope with the abnormal growth of displaced people, but those providing medical assistance and promoting water, sanitation and hygiene activities in the area say they have seen a deterioration of conditions. It is a population that is becoming poorer and increasingly dependent solely on the humanitarian assistance. We enter in a restaurant to have a quick meal and I notice that some adult men follow us in. They are well dressed but they are in search of food. They sit near us, they wait for us to finish and then ask us if they can clean our plates. This isn’t unusual. Restaurants often have people like this. They are not beggars, simply adult men in search of food. There is no shame in it. They sit quietly; they don’t bother us. Even the owners of the restaurant tolerate them as they wait for the leftover rascius—a white bread.

The news reports talk of a potential famine and pockets of malnutrition. Malnutrition is clearly getting worse. The governorate of Hodeida is one such area. And in the norther town of Sa’da, where I travelled last November, I went to a hospital where next to rooms filled with wounded young fighters was an entire department dedicated to treating malnourished young children. Many had travelled from the nearby border with Saudi Arabia, where some of the heaviest fighting has occurred. Accurate statistics are difficult to collect, but the U.N. believes at least 2,000 children have already perished from malnutrition while another 1.8 million children are classified as “at risk” of receiving inadequate nutrition.

The deaths of children are especially sad and usually occur in a hidden corner of a hospital or in some poor neighbourhoods. Something very different are the funeral processions which I witnessed in Sana’a, where the remains of young fighters are driven through the town usually on top a vehicle painted fully in green and surrounded by families and young fighters singing chants in honor of the fallen.

Beyond such events, the deeper truth is that country seems to hover on the brink of collapse. The lack of a political agreement between warring factions in the present conflict and the fact there seems to be no sign of achieving peace anytime soon will only deepen Yemen’s critical need for humanitarian aid. Many Yemenis are so exhausted they no longer seem to care about the outcome. They simply want the war to end. As the third year of war approaches we are confronted with the unsettling reality that before peace is achieved, there will be more quiet deaths of young children, more parades for fallen fighters and a growing need for international humanitarian assistance to ease the plight of Yemen’s long-suffering population.

January 10, 2017 – Blog Entry #5

As we fight to help the sick and injured, delays can cost lives

The devastation wrought by the civil war slows our efforts to help those suffering in a country scarred by years of conflict.

For a country that carries the deep scars of years of vicious conflict, where events can develop by the minute, it is often easy to feel that nothing changes very fast. The celebration of Mouloud brings rare moments of joy, celebration and a vivid and vibrant green to the streets of Sana’a. Banners, flags and vehicles are daubed in the intense color, marking the birthday of the prophet Muhammad and providing a tangible milestone for the passing of time.

We nose our vehicle towards the first checkpoint on our journey south out of Sana’a on a road that will take us to Aden — a routine journey in order to monitor the work of International Medical Corps teams across the region. The state of the country makes such trips both tense and dangerous but also laborious and dogged by administrative hurdles — a bizarre combination, and one that makes traveling so very slow.

This arduous pace is clear when we reach the main checkpoint of Yasleh in the Bilad al-Roos district, the queues swelled by visitors to the country’s capital. A soldier gives a blase wave of his machine gun as he tells us to wait for official wheels to turn.

“Go sit in the restaurant. We will call you when your pass is ready,” he says, as he lights a cigarette with his free hand.

This is standard, and is going take time. I sit in a plastic chair and watch merry Yemenis arriving from all districts. Most have clearly come from the villages and districts around Sana’a. Many wear military uniforms and almost all carry a Kalashnikov.

Ahead of us are the towns of Ibb, Taiz, Lahij and Aden, notorious because of the violence that has been taking place there. In December alone, the latest attack in Aden saw a bomb kill 49 Yemeni soldiers in front of the al-Sulban military base, while subsequent fighting pushed the toll higher each day.

A wave by my logistics coordinator indicates that we have the green light to proceed, after a call from the depths of the country’s national security apparatus convinces the security guard to open the door to Ibb to us.

The scenery is beautiful, and the chance to see it is one of the best parts of my work. We pass mountains, rolling countryside and unique old houses built of rough stone — common in Yemen but rare anywhere else. It is a privilege to explore areas that most will never see, which even TV images rarely capture.

But we need to slow down as we pass craters left by bomb blasts, creep past rubbish bags ignored for months, and navigate the rubble of devastated buildings. In every area here, the war has taken lives, ruined basic infrastructure and stolen possessions.

As the hours pass, many soldiers manning the regular checkpoints can barely speak, their mouths full of the local amphetamine-like stimulant, khat, which causes one cheek to blow up like a small balloon. Many are as young as 13, all are skinny and all have the Arabic quotes denoting their role as “helpers of Allah” on the butts of their assault rifles.

Our progress is slow, and helps to explain the problems our mobile medical teams face as they struggle to reach our health facilities, which are under constant pressure. In Ibb, many of those who have been forced from their homes wait for the fighting to end, desperate for food, shelter and medical support.

We stop for a night, preparing to leave again at first light. From there, we head towards the Al Dhale district, passing more and more checkpoints — some small, some formal, some manned by soldiers wearing Cossack-style greatcoats — some just a few hundred metres from the last. We’re nearing the frontline, and the nervous tension mounts.

The same gestures are repeated over and over, the same questions are asked and hours are lost waiting for phone calls from Sana’a to vouch for us and permit us further passage. The final checkpoint of the north is much like all the rest, then suddenly new groups are manning the checkpoints in the south — little in the way of fuss, but bringing new questions.

“Any Russians or Chinese? Are any of you Russian or Chinese?” a soldier screams, before collapsing into hysterical laughter and receiving the applause of his colleagues. Having swapped cars to travel with our Yemen-south team, we drive off, leaving the soldiers behind in giggles.

It is afternoon when we reach Aden, and the incredible blue of the sea welcomes us to the city. It reminds me of the sea of green we left in Sana’a, and it is stunning in its beauty. We travel to a heavily guarded area on top of a hill known to locals as al-Maashiq and an amazing panorama unfolds; pristine beaches and a clear sky provide a feeling of peace and beauty — so elusive in this devastated land.

We have come to sit with the prime minister of Yemen, Ahmed Obeid bin Daghr, and the governor of the local area.

We are here to present to the authorities the challenges for humanitarian workers in such contexts, the impact of the security situation on the teams who are dedicated to helping the most vulnerable, and the need for support to let us carry out the work our donors have charged us with completing.

It goes well, or so I think, and my team departs, hopeful that some impact has been made. As we return to our office in the city, we pass what should be happy scenes of people shopping around the main road of Queen Arwa, families playing with young children and old men playing chess on the streets — but all amid the stark remains of buildings burned and dark, their contents looted. Armed fighters idle in the shadows, alert, on edge and menacing.

Amid the beauty and busyness of lives being lived, at our hospitals and medical clinics our staff see young people queuing up for help with shocking war-related injuries. Some come to us almost completely burned from head to toe, while mothers bring young children who are severely malnourished and on the edge of death.

A dark past looms over a shaky present, where frontlines shift, loyalties change and alliances are made and broken — and in the middle, millions of people try to live their lives as best they can. There is no end in sight, and the fear is that even the most basic services supporting these people are finally set to collapse.

In such a fluid environment, speed is often the difference between life and death. Speed is being denied to humanitarian organizations like ours, a denial that makes a hard job all the harder for my teams of dedicated people. Each time I wait at a checkpoint, I consider it part and parcel of life in this most chaotic and dangerous of places. Each time I try to put out of my mind the true cost of such delays — a cost that can be measured in terms of lives lost rather than minutes wasted.

October 28, 2016 – Blog Entry #4

A Journey To Sa’da

Editor’s note: Yemen Country Director Giorgio Trombatore is based in Yemen’s capital of Sana’a and is responsible for a country team of more than 150 staff members and for programs we operate from offices in Aden, Taizz and Sana’a that provide humanitarian assistance to those in need. He recently accompanied a convoy carrying medications and other supplies that International Medical Corps delivered to a hospital about 100 miles away in the northwestern town of Sa’da. This is his account of the trip.

On a late October day, we reached the town of Sa’da in Yemen’s far northwest with a feeling of accomplishment. We had managed to arrive with a convoy of trucks carrying much-needed medications donated by the U.S. Government’s Office for Disaster Assistance (OFDA).

The journey to Sa’da from our main office in Sana’a, the capital, is only about 100 miles, but unstable and unpredictably dangerous security conditions along the route required us to plan the trip carefully. Air strikes have been especially heavy throughout much of northern Yemen since open conflict broke out in March of last year. Prior to leaving I pored through humanitarian reports about the war in the north. It was no secret to anyone that Sa’da had been targeted frequently I had a chance to discuss our mission on several occasions with local authorities there and most issues related to the trip had been resolved, but we were advised to delay our departure in early October as security conditions deteriorated after more than 100 were killed in the bombing of a funeral ceremony in the capital.

Finally, we received the green light from local authorities in Sa’da and set off for the north with a convoy of three heavily-loaded trucks, accompanied by a small team of physicians and our logistics specialists in addition to myself. I could tell the staff was excited about the journey. Many of them had never visited Sa’da and weren’t sure what to expect. The security bulletins were a cause for concern, with reports of escalated fighting along Yemen’s northern border.

Despite those reports, the first part of the trip was quiet and calm. The road was also more accessible than going south from the capital toward Taizz where the presence of constant check-points could turn a short trip into a seemingly endless journey. As we approached Sa’da the signs of war—destroyed bridges and burned out trucks—gradually became more frequent.

Sa’da is located in a very dry part of the country amid barren mountains at an altitude of more than 6,000 feet, yet it is home to some very beautiful sights that were visible from the car windows as we entered the town. But so too were the ubiquitous and unmistakeable signs of the war. The town itself is small (its pre-war population was around 50,000) and damaged, often destroyed, buildings were a tragic sight for any passer-by to see. Most all government buildings had literally been demolished with damage extending into the historic old town with its narrows roads, the public bath area, and the streets around central mosque littered with debris. A more modern part of the town’s outlying areas had been completely levelled. While the focus of our work and that of other international humanitarian groups is on the human toll, a look at Sa’da is a reminder that we are losing important elements of our world heritage as well. The reality is that parts of a great civilization are disappearing—an irreplaceable loss for this generation and those to follow.

But the most powerful memory of the trip was the silence of many young fighters. I never saw so many young people gathered in a single room show no sign of life. The only sound was a deafening silence. As I entered Sa’da’s main al Jumhouria hospital where some of the medicines we had delivered were being distributed, I had a chance to accompany a local doctor as he made his rounds, visiting the patients—all of them there because of injuries sustained in the war. Far from the streets of Sana’a where life tends to goes on with only minor interruptions, I was now face to face with the harvest of this conflict.

There were hundreds of young Yemeni boys, averaging maybe 16 or 17 years-old—it was difficult to tell the exact age of those lying in hospital beds. All were silent. There were no screams of pain, of anger or of desperation. Only silence. The day I visited the hospital was a normal busy day for a medical facility that receives many new wounded daily.

I turned to my colleagues who were accompanying me and shared my thought: how is it that only in this moment are we reminded of the true reality of being in a country at war. An average of twenty or so wounded arrive at the hospital daily. As I left one area to enter another, I saw overwhelmingly young people. From time to time I would see an elderly man, but it was the exception. It was a sharp contrast to the hospitals of Europe and the United States where mainly older people are being treated. Here they were all so young, so quiet and still. It is an experience I will not soon forget.

The doctors introduced me to every patient. Invariably they nodded, acknowledging questions with a simple yes or a no reply. Many were amputees, some had burns. Most were victims of bombing. Some patients had family members sitting on the floor around them. Others were completely alone. All wore an ID bracelet on their arm so they could be identified if the worst happened.

I was astonished to see a young boy sitting on a bed next to his father. The father’s leg had just been amputated. I could sense a desperation in his eyes but at the same time a certain dignity. The nurse told me the same boy had been hospitalized the previous month when his arm was amputated. I hadn’t notice the missing arm initially. Only when he lifted his jacket could I see the empty space where his arm should have been. The sight of father and son together was a powerful image. They both looked at me, clearly a foreigner, and said nothing.

In another room, I saw a young boy standing half naked in the middle of the room, his face completely burned. Initially, I did not want to disturb him, but I also could not to pretend he wasn’t there, so I approached him and asked how old he was. He told me he was 16 and as he spoke I could see he was losing the skin from his face. He said he’d been injured in a bomb explosion.

Finally, we entered a ward for malnourished children. Here a very animated doctor welcomed me. Mothers or other relatives sat close to their little ones. Many had come from villages close to Yemen’s border with Saudi Arabia. Most of the health centres there had been destroyed so these mothers had come to Sa’da. The paediatrician told me some mothers had waited too long. Many children had failed to survival the journey and had died along the way.

The hospital treatment areas were well kept, clean, and the staff seemed pleased by our visit. They could see the trucks being offloaded and felt relieved that some aid had arrived. Later in the day, we met with local health officials at a local restaurant which was filled with customers. Young men came and went—all wearing typical Yemeni dress. All were armed. At one level it seemed surreal—like a scene out of an old “Lawrence of Arabia” film with the traditional dress and the intense look in the eyes of the young men. I realized that some, possibly many of them, could lose limbs—or their lives—before reaching adulthood. If they were lucky, they would be identified by the bracelet each wore on their arm.

September 2, 2016 – Blog Entry #3

Reflections of a Year in Yemen

Editor’s note: Yemen Country Director Giorgio Trombatore recently completed his first year managing the International Medical Corps team in Yemen. Based in Sana’a, he is responsible for a country team of more than 150 staff members and for programs we operate in Aden, Taizz and Sana’a that provide humanitarian assistance to those in need. Earlier this year he wrote about his trip by road over 400 km (250 miles) from Sana’a, to visit the organization’s office in the southern port city of Aden. With flights between the two cities suspended because of the country’s civil war, the only option was to drive. Below are his reflections of the challenges he has faced to direct International Medical efforts to support tens of thousands of civilians caught up in a civil war that seems to have no visible end in sight.

Following months of relative quiet, the bombing has resumed in and around Sana’a. It’s a reminder that a full 17 months after it first began, the war in Yemen is far from over. When I first arrived here a year ago, it was common practice to have the night disturbed by aircraft flying over Sana’a. They dropped bombs that sometimes were so powerful the building shook as the blasts sucked the air out of the surrounding darkness.

Everyone seems to agree the conflict here is entering in a new phase. As I went on my routine visit to the central prison of Sana’a recently, I found myself thinking about what it is like living in a country at war. Once I entered the main gates of this structure and reached the area where prisoners affected with mental illness were gathered I noticed it was full of prisoners of war from the south. They were all gathered in a square within an open block. I was surprised because they were not in their usual cells but were standing there in the open. Many of them just idling, others sitting, others smoking. All seemed to be waiting for something—anything—to happen. Many were very young, others a bit older. All gave me the impression of restlessness. They walked around the compound, up and down trying to kill the time. I could not but recall that I had seen a similar scene many years back in 1995 in Kigali (Rwanda) where prisoners had been rounded up, then forced to wait while authorities decided what to do with them and where to put them.

As I passed through with my usual group of guards and doctors I was curious watching the signs of a war that is there–that is all around us, even though in my daily routine it’s sometimes easy to forget the context in which I am living. I think is a very human reaction to adapt to the realities in which you live. The brain seems to be able to adapt even to the cruellest situations. I find I no longer even notice certain things that would shock any visitor. Like old wallpaper or background noise, they have become part of my life here. When I travel to a meeting, I know that around me I will see destroyed buildings, that I will pass through check-points manned by gun-wielding youths barely in their teens. I’m no longer concerned when I receive alarming news that keeps on coming to us about the frontline getting closer to Sana’a, about air strikes or ground operations in the country. Everything is so quiet for me, so strangely quiet. When the weekend comes, this place is especially quiet. Only the noise from our generator breaks the peace of the Fajatan suburb. When I look over the rooftops to the town below, I see kids playing in the streets and the deserted park of Fajatan, full of cats searching for food in the debris. It is quiet–a good atmosphere for reading and thinking.

I have to confess I struggle to understand the political situation. Even after a year, It remains a mystery to me. I wonder how people from abroad sometime seem to be so sure about everything. Where is this knowledge coming from? I ask myself so many questions and yet so much remains unanswered. Just one example: How it is possible that an entire city is inaccessible, cut off from the world around it? I mean really, in 2016?, How it is possible to isolate Taizz, Yemen’s third largest city, a city larger than Atlanta and twice the size of Verona, one of the most famous cities in Italy? Over half million people. How do you explain that this town has been closed off to the outside world for more than a year, that it’s impossible to provide residents there with food, medication or other humanitarian assistance? The closest I managed to get to Taizz was earlier this year and I was surprised to see that there was a de-facto wall made of sand-bags separating it from the surrounding areas. The barrier looked formidable. This is difficult to comprehend, especially because as you approach Taizz there are restaurants, taxis, markets, and busy streets all around. Then suddenly nothing. Silence—a city, alone, seemingly forgotten, abandoned to its fate. Believe me it is difficult to comprehend this.

I recently met a very high profile senior politician. He was pretty old and I guess he was in that time of his life when you don’t believe in just words, ideological slogans when your life has seen so much and you start to become cynical about humanity in general. I had a nice conversation with him, I shared with him the challenges of my job and dealing with the arbitrary nature of power and of those who wield it. Prior leaving his studio the old man told me, “you have to learn to be resilient and patient. We are living through tough times in Yemen. People have to work on their negotiations skills”. On my way back to my office weaving through the ruins of Sana’a suburbs I kept on thinking of his words: “learn to be resilient, work on your negotiations skills”.

The more I thought about this, the more I wanted to tell the old man,“ Spot on“. His words are very true and his advice good—especially since the range of our activities and the deployment of our staff are growing as new potential areas open in Hodeida and Hadhramout. If this expansion is going to succeed, we’re going to need to strengthen the network of our connections and improve our negotiating skills. If we don’t, our mission could become vulnerable. The level of issues and the problems they bring tend to increase as we expand the geographical areas of interventions. New leaders, new groups, new personalities to meet, to understand and to find the lines that cannot to be crossed.

Along with this tightrope walk, the main role of the Country Director is to provide guidance for the team and make sure it keeps its focus. I have great respect for this team. I try as much as possible to listen to them, to sit with them and hear their challenges, their concerns.

How do they view what’s happening in Taizz—one part in the frontline of a long war that goes largely unnoticed in the West? How are the people around me being affected by this? Have they lost hope? Certainly none of them want this war to keep going. They are concerned about their lives and most of all about the future of their children. They follow closely the Kuwait peace talks but without putting too much hope in them. They seem ready for more retaliation, more pressure, more difficulties doing the simple things in life like getting the propane gas bottle for their kitchen. They also seem braced for more air strikes, more suicide bombing attacks. Most of all, they feel the sense of isolation that is so strong in this country.

Most all airlines have suspended their service to Yemen. Only a few UN flights (which are only for UN staff) and Yemenia Airlines continue to operate flights in and out of Sanaa. Once in Yemen, travelling from one town to another is a massive organization nightmare. Travel permits have to be submitted three days in advance and sometime they alone are not sufficient. In areas close to the frontline the militia forces get more nervous and travel papers, even if they are in order, may not be enough ensure passage. Conditions in Aden, where our mission is located that serves the southern-most areas of the country, can be even more arduous. Because of security issues at Aden’s airport, reaching the city requires a long boat trip from Djibouti. Killings and targeted assaults are common in the south. One of our mobile teams there was recently fired upon because they failed to include a specific village on its route. The incident tells a lot about the level of violence—and the culture of violence—in which our teams operate.

Despite all of this, Yemen amazingly still remains a land of smiling and beautiful people. During my year in Yemen, wherever I’ve travelled, I have never confronted any kind of particular anger or hate toward me. Only true hospitality and smiles from people you can see are mild and love life in a way I never experienced at home in Italy. Sometimes in Sicily if you look in the eyes of someone too long it can lead to a fight, but when I mention this to my Yemeni colleagues they all laugh at me in disbelief. On occasion, I have seen the mood soften within minutes. It often happens when I enter the prison, where the guards initially are very stiff and strict. They question what I am doing there. They want to control whether we take photos or when we ask questions they want to record it. However, once I sit with my local artist and we start to chat about works of art, the guards themselves forget their role and join very happily our discussions.

I can’t deny those are still best moments I’ve had here because they enable me to see the place in a different light. Sana’a is starved of color. Everything is debris. Plastic paper is everywhere. But when I sit with talented young artists here in Sana’a I enjoy seeing a different reality through their perspectives and their eyes. I can also understand their limitations and frustration. Imagine if you were an artist in a country where there wasn’t enough food and no medicines at all, do you think people would care about your art, as busy as they are struggling to stay live? I have met many of them and with some of them we even worked on some beautiful projects inside the prison, as well in our compound that is now used as an open “exhibition” where artists can work. That may sound strange, but when you think about it, it’s important not to lose that part of life.

I wish there was greater international understanding about what’s going on in Yemen. I am not one of those people who complains because there more focus on a killing in Belgium than a full-scale battle in Taizz. I understand that the depth of interest and emotions are not always related to the size of an incident or to the level of injustice. People in my home country of Italy have no idea that Hadhramout is a region in the southern part of the country. They only know Yemen as the place where the biblical kingdom of Sheba once held sway and where the famous Queen of Sheba once ruled. So it is normal that If I live in Sicily I am more shocked about an act of terrorism within my own community than by something happening in a far off country called Yemen.

But now I am in Yemen and of course a massacre in Taizz touches me more than if it had occurred a few years ago when I was serving in Afghanistan. At that time Taizz would have been just a name on a map to me, much as it is for so many who live outside the region today. But not for me. Now I am here. Now I am part of this, I eat with these people, I see them struggling and I cannot help but sympathize with their plight. It is human. It is natural to feel that way. I would like to be able to voice their needs more broadly. Perhaps one way of doing this is to give opportunities to local artists to express their feelings whenever I can.

March 1, 2016 – Blog Entry #2

Editor’s note: International Medical Corps Yemen Country Director Giorgio Trombatore recently travelled by road over 400 km (250 miles) from his base in the capital, Sana’a, to visit the organization’s office in the southern port city of Aden. With flights between the two cities suspended because of the country’s civil war, the only option was to drive–a trip that carries more than its share of security risks in current conditions. The route itself is a tour through the tragedy and hardship that has become everyday life for the millions of Yemenis affected by the civil war that tears at their country. His account of that journey follows below.

In today’s Yemen the real borders are its checkpoints. There are so many militias and military groups that the country’s internal political map changes shape daily—not to mention the larger political divide of Yemen’s civil war. In order to get a sense of this just travel the country by road. The trip to Aden was organized in close consultation with our security team, carefully reviewing all options and possible routes.

The challenging part of the trip began roughly at the half-way point, from the city of Ibb, 190 km (120 miles) south of Sana’a, where International Medical Corps operates a large sub-office. The staff there works long hours to assist thousands of displaced civilians who have sought safety in Ibb after fleeing heavy fighting in neighboring Taizz. On an early February morning, we set out from Ibb in two vehicles heading for Aden.

When we left I was unsure what type of security measures had been worked out with the various militias that control sections of the road along the way, but I was relieved to find a team from our Aden office waiting for us in a small village that was the final outpost of Sana’a government controlled territory—an important fault line of Yemen’s civil war. The Aden staff members would escort us the rest of the way.

The staff had brought two people with them who would help us along the way–one bearded, with a turban and striking eyes to help us cross into the south and get us through armed checkpoints on the long desert road into Aden. A second, shorter man, would manoeuvre us through the various checkpoints inside Aden city, a place controlled by a bewildering mix of groups, each with their own loyalties and political agendas. Adding to this confusion, conditions on the ground along our route were constantly shifting.

It was late morning when we crossed out of Sana’a controlled land and entered the South Zone. We immediately spotted a southern fighter armed with a Kalashnikov rifle standing in the middle of the road, waving down vehicles, then leaning in to demand identification. The check-point here was different—not the kind I had grown accustomed to in the north, with soldiers constantly waiving annoyed drivers to pass. Here, tension was high. Everyone knew this was a frontline where attacks were frequent—as I would discover for myself few days later on our return trip.

The southern militia fighter was looking for those coming in from the north, but as our turbaned facilitator leaned out and waived, the fighter simply stepped aside and we were on our way again. Our companion was a living passport and good at his job. Members of our local staff from Ibb and Taizz were visibly delighted having him along—an obvious person of influence and authority among local fighters.

The Aden road is beautiful, a constantly-changing landscape of palm trees and desert littered with abandoned military vehicles. The route also had checkpoints every mile or so, invariably manned by militia fighters dressed in long Soviet-like coats similar to those worn by soldiers in Sana’a. Our turbaned facilitator’s smile and easy manner carried us through each checkpoint as we continued our way south. I soon realized that in this part of Yemen my own long beard seemed to draw more approval than in the north, with wide-eyed militia guards occasionally asking, “Who is this?” Men with long hair and flowing beards were also visible in far greater numbers in this part of Yemen than in the north.

The last section of road into Aden ran through a desert home to little more than an occasional destroyed tank. As we approached Aden our turbaned desert road guide suddenly asked to stop. With ceremony he got out of the car in what seemed the middle of nowhere, bid us farewell and our Aden facilitator took over. Once in Aden, we found it much harder to move around, in part because the checkpoints could not be clearly identified. More than once I was told the militiamen that we had just passed belonged to Al Qaeda.

Aden has a beautiful setting, with the sea and mountains both so close. But the town itself is in ruins. Large buildings had been bombed, destruction lies everywhere. Little has escaped untouched. Government buildings and hotels–obviously targeted–were now only debris. One can only imagine what Aden once was. Amid all this, there were also signs of reconstruction underway, largely undertaken by Saudi Arabian or other Gulf State companies. At one point off a road littered with destruction, a newly-rebuilt school appeared, walls freshly painted and photos of Gulf State dignitaries decorating the entrance.

I was particularly pleased to meet members of International Medical Corps’ Aden team in their own city. The day after my arrival I was able to visit some of our programs, including the Al Sadaqa Hospital located in an area of the city where security concerns remained a major issue. During my visit, three member of the controlling militia group followed us around, led by a pudgy young man with a turban and long side curls. All three carried new weapons and made it a point to stay close as the hospital director, clearly nervous, led me around the facility. Only later did I discover the militia group deployed around the hospital was comprised of Al Qaeda fighters.

Although once used as a shelter for internally displaced persons (IDPs), I was impressed by how clean the structure was. International Medical Corps pays over 80 % of staff with incentives and also provides medical supplies and equipment. I was also impressed that despite the civil war and broader instability in the city, International Medical Corps remains an active team of genuine first responders.

We then visited the Al Jumhouria hospital, a trip that required several diversions through the city along the way. Large numbers of militia forces were deployed on the streets, but who they belonged too remained unclear. I was welcomed to the hospital by an 11-year-old boy standing by the entrance armed with a Kalashnikov rifle. I was surprised to see him there and made a note to notify the director. It is one thing to see armed children along the desert road, but quite another to have them at the entrance to a hospital receiving millions of dollars in support from international donors.

The hospital was jammed with people and boxes of supplies and equipment were stacked outside. I was heartened to learn that the facility had managed to bring in doctors from India to train its surgical staff. People crowded the corridors, which was understandable since Al Jumhouria was one of the city’s main referral hospitals. Wounded militia fighters were brought here and I could see many of them occupying beds in an emergency ward.

My most interesting meeting was with the governor of Lahj Governorate, the administrative area that borders Aden. To meet him required passing along the same road where just weeks before the governor of Aden had been assassinated. The route hugged the sea front where it was possible to envision how Aden must have been in better times with its beautiful beaches and pleasant restaurants. An elaborate church was visible and I was told there had also been a synagogue in the area. Now there is only debris, poverty and weapons of war.

The governor of Lahj, only recently appointed, was gracious and soft-spoken. He received us in a small office. We were told that only a few weeks earlier he had escaped his own assassination attempt and during our conversation he used the words, “mashrou maout” to describe his work—an Arabic expression that could be roughly translated as “a project of death”. I had no idea of his agenda but he seemed prepared to sacrifice his life in its cause.

After finishing my business in Aden we began our trip back to Sana’a, only to be reminded how difficult it can be sometimes to move in Yemen. Traveling with the same turbaned facilitator who proved so effective on our trip south, our initial goal once out of Aden was to drive north until we could leave the southern zone and reach the first check point on the northern side of the civil war’s divide. Two hours into the drive, we were halted by an airstrike on a section of the road ahead. As we waited for the bombing to end, fighting between opposing forces erupted at a checkpoint nearby. We waited in a small village, not knowing whether to proceed or stay put. As we sat, we saw people moving towards us from the direction of the fighting. A fast-moving vehicle arrived with a wounded soldier who was transferred to a pickup truck for evacuation to a nearby hospital. In that short skirmish, 5 people had died, all young soldiers, whose lives had suddenly become statistics in a seemingly endless war. Although I was a rare foreigner in this area, my presence was largely ignored. The fighters were focused on the war.

The following day we decided to take an alternative road, this time over a large mountain where people with no alliances to militia groups lived, something that enabled us to travel without a facilitator. The trip through this part of Lahj Governorate was relaxing. Tensions melted away as the scenery provided a sense of just how pleasant life in Yemen could be. We passed through villages and markets where there were few—if any—weapons visible, where children were going to school, people were busy in the markets and you could see women and men walking side by side with donkeys. The villages were beautiful, unlike some of Yemen’s towns overwhelmed with concrete and the plastic paper needed to wrap kat, Yemen’s alternative to chewing gum.

As we continued north, conditions changed once we reached the Al Torba region. Here again militia forces were visible in large numbers and after passing through the last checkpoint before re-entering territory controlled by the government in Sana’a, we found ourselves on a road that seemed under no one’s control—a sort of no man’s land where vehicles were told to drive as fast as possible to avoid snipers believed to be in the area. Finally, we were stopped at a checkpoint, this one controlled by Sana’a government forces. Our journey to Aden was nearly over.