Editor’s Note: International Medical Corps’ Yemen Blog presents a rare view of life in Yemen, chronicled by our first responders as they battle one of the world’s worst humanitarian disasters—one fueled by poverty, hunger, disease and years of Yemeni factional fighting that erupted into a full-scale civil war in 2015 involving other countries in the region.

The entry below is written by Dr. Salah Addin AlQadhi, a Senior Medical Officer at our office in the Red Sea port town of Al Mukha. Dr. Salah was born and studied medicine in Yemen’s third-largest city, Taizz. After working in general practice for about four years, he joined International Medical Corps in 2021. His duties include working with one of our mobile teams to provide medical and nutritional care in remote, rural areas, and to strengthen awareness about the importance of good sanitation and hygiene practices.

Vaccination is one of the great accomplishments in public health. Immunizations save lives, reduce morbidity, mortality and healthcare costs. But to be effective, vaccination programs must have high rates of coverage. When coverage rates fall, disease can spike quickly. Because of this, a global immunization strategy developed to achieve the necessary coverage relies heavily on routine visits to communities, wherever they may be, to keep coverage rates high.

In Yemen, that’s a problem. Long years of war have disrupted the supply of vaccines and blocked access to large sections of the population who live in remote, rugged areas that are difficult to reach under normal conditions. In times of armed conflict, the task can border on the impossible. Predictably, vaccination coverage rates in Yemen have fallen during the war years.

In parts of southwestern Taizz governorate where I work as a medical officer heading a mobile medical team, official goals to vaccinate 95% of the population nationally and at least 80% at each district level seem unrealistically high, in part because the collective damage of nearly eight years of war has been so bad here. The scars left by some of the heaviest fighting are easy to spot. The emotional damage to residents and wounds to the region’s social fabric are more subtle. War has led to the near-collapse of Yemen’s national health system in many areas—more than half of the country’s healthcare facilities no longer function. Still, we refuse to give up.

To increase vaccinations rates in the region, we now have four mobile medical teams based at Al Mukha District Hospital in the area’s largest town: the ancient Red Sea port of Al Mukha. The teams travel to smaller settlements up and down the coast, as well as to outlying villages and displacement camps in the desert to the east. The roads we use have suffered, both from war and from neglect. They are deeply rutted and barely passible in places.

Many small side roads leading to villages further into the desert scrub carry markers warning of unexploded landmines that remain scattered just off the access route. To reduce travel along such roads and diminish the chances of accidents, we now make vaccines meant for children and pregnant women available in nearby villages and camps for internally displaced persons (IDPs) that have proven to be free of mines and other explosives. Such tactics help us meet another important priority of the mobile medical units: to reduce the dangers and preserve the safety of local residents—especially children.

Although a UN-negotiated ceasefire agreed to last April remains largely in place (despite the recent collapse of talks to extend it), the return home of many of those displaced in earlier fighting has brought its own problems. Landmines and other unexploded ordnance triggered by unsuspecting returnee villagers and displacement camp residents have claimed scores of casualties, including children. The resulting fear of straying too far from home has dampened hopes for any significant rise in vaccination levels in the near term.

Our teams also find it hard to counter other sources of resistance to immunization, including illiteracy, suspicion and fear.

The implications of low vaccination rates in this part of Yemen are considerable and extend well beyond the Al Mukha area and the borders of Taizz governorate, where vaccine-preventable diseases—including measles, dengue, and diphtheria—and the risk of polio are simple facts of life. Collectively, they pose a heightened public health risk—not just for local residents, but to the broader region that includes other areas of Yemen further north and east, as well as to nations that lie west across the Red Sea in East Africa. From Al Mukha, Africa is only 30 nautical miles away. These high stakes have only motivated us to further intensify our efforts to increase the immunization rates.

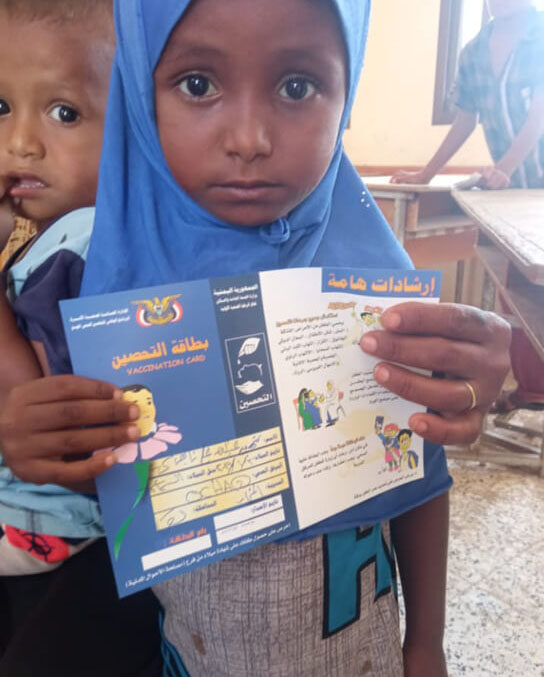

Today, the health facilities we support in the coastal districts provide vaccination services against communicable diseases such as polio, measles, diphtheria, and pertussis, as well as COVID-19. At the same time, our four mobile medical teams based in Al Mukha district now travel regularly to so-called “outreach” villages—mainly inland from the coast in remote areas of the district— where they offer immunizations and other routine health services to residents and to those living in IDP camps, who otherwise would receive little or no medical care without travelling long distances.

We have also recruited, trained and deployed groups of local residents as community health workers to encourage good health practices—including immunizations, stressing the protection they give and the diseases they prevent. Because they are known locally, they have the public’s trust. We have a long way to go, but early indications tell us the strategy is having an impact.

We knew that, before we began serving these remote areas directly, most children did not receive any vaccines until they were two or three years old. When I go to these villages today, it makes me happy to see many children in their first year of life receiving their vaccinations thanks to the work of our mobile teams and the community health workers. Our regular visits to these communities, plus the messaging of our health workers, have also help remove some of the mystery of a vaccination—and with it, much of the fear surrounding it.

We have a long way to go, but now we feel we’re making progress.

View next blog:

Daring to Dream