In the midst of the West African Ebola outbreak of 2014–2015, International Medical Corps teams developed a simple but effective low-tech way to detect the highly contagious virus early. Now, we are adapting that same idea in many parts of the world to track and contain the spread of COVID-19.

Known as screening and referral units—or, as they’re more commonly referred to, SRUs—they began as little more than a table, a chair and a patch of shade to protect screeners and patients from the sun, placed at all entrance and exit points to hospitals, clinics or other health facilities. They were staffed by one or two health workers armed with electronic thermometers capable of quickly spotting Ebola’s often-invisible calling card: a high fever.

Screening all entering or departing these facilities, the process became a formidable tool in identifying Ebola cases early—a key to stoppings its spread. At the same time, it restored public confidence in state-owned healthcare facilities, largely abandoned by a wary general public convinced that the virus was rampant in hospitals and clinics.

A few years later, we again used SRUs effectively in the fight to contain the world’s second-largest Ebola outbreak, which began in the late summer of 2018 in eastern areas of the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC). Today, we have deployed them to confront COVID-19, screening thousands for the virus each day in Africa, East Asia and the Middle East.

In South Sudan—where heavily populated areas in and around the capital, Juba, sit just across the border from the DRC—International Medical Corps began operating SRUs in mid-March at all UN-controlled entry and exit points to two protection-of-civilians (PoC) camps, which act as sanctuaries from the conflict that has been plaguing the country for more than seven years. We also monitor foot traffic in and out of other UN PoC zones in the country, including the northern town of Malakal and Wau to the west.

“We’re screening about 2,000 people or more a day,” explains Dr. Abdou Sebusishe, International Medical Corps’ medical lead for COVID-19-related matters in South Sudan. He expects that number to rise as the country team adds staff to screen traffic passing through several smaller, unofficial crossing points that have developed over time at the two Juba protective zones. They also plan to extend screening hours in Wau.

“The idea was there in case Ebola crossed the border from the DRC,” Abdou says. “We were lucky Ebola didn’t come, but now we have a coronavirus, so in February we decided to convert it to a COVID-19 facility.”

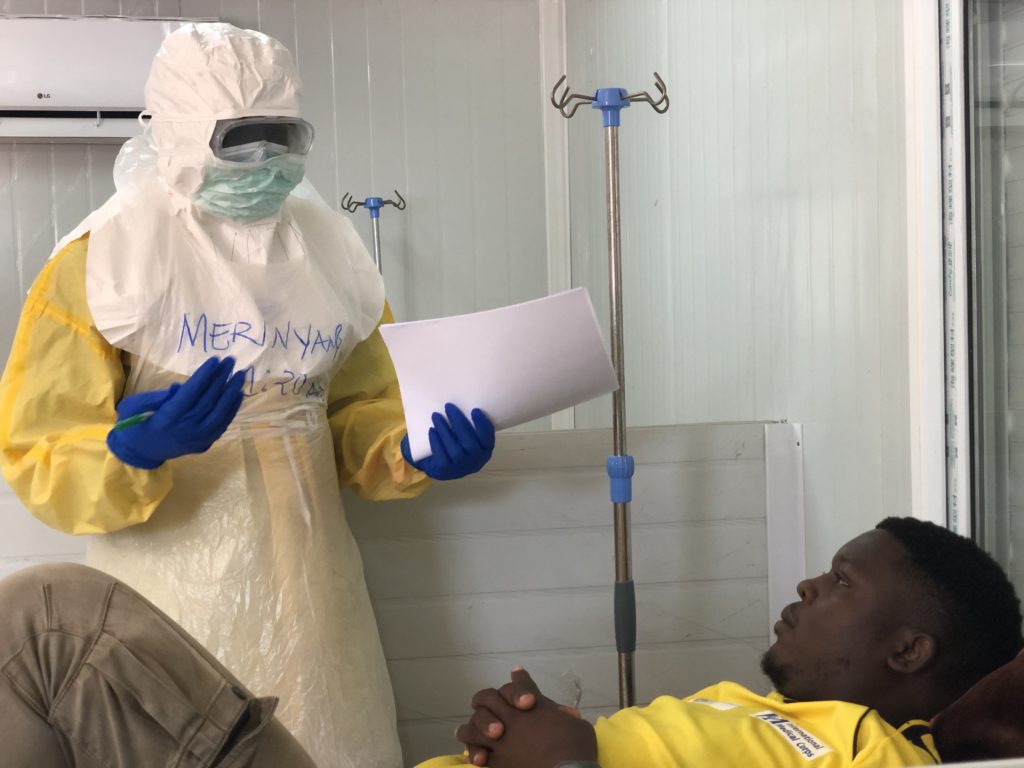

He explains that if someone registers a fever, they are asked to rest for a few minutes in a nearby area shaded from the African heat before being rechecked. Though often that is enough to return elevated temperatures to normal, if the fever persists, a medical team based just a few minutes away, dressed in protective gowns, gloves and eye shields, escorts the person to a temporary isolation unit for more detailed symptomatic screening and a recent travel history—a step that, for light or moderate illness, can lead to a request to self-isolate. In more severe cases, it requires a test for COVID-19 and eventual transport by ambulance to an infectious disease unit (IDU) half an hour away that we operate.

Abdou says his team is working to increase messaging and other communications about COVID-19 to build greater public support for the screening, to counter the common complaint that screening is just a waste of time. The messaging stresses how simple temperature-taking provides important protection for the community.

“Understanding is growing,” he says. “People have stopped insulting screeners, but we still have more work to do for people to realize it protects for the community.”

Abdou also expresses concern about capacity of the 100-bed IDU in Juba, given the rapid spread of the virus, as well as the 30-minute-plus ambulance ride from the screening area—a distance that leaves both patients and their families who reside in the PoC camps both far from home and away from the protection that they have come to expect.

“Those who live in the protection zones are more confident if they can be treated there,” says Abdou. “They are not confident if they have to walk miles to seek medical help. That’s a major challenge.”

Other International Medical Corps programs using SRUs include Ethiopia, where our team screened nearly 5,000 patients in more thinly populated areas for the virus during a one-month period at facilities that we support. During this time, we sent 107 suspected cases to government quarantine centers for testing and further treatment.

And in the Middle East, our team working at the Azraq refugee camp in Jordan has set up an SRU to measures temperatures of all who enter and leave the camp, which has a population of more than 35,000 refugees, mostly Syrian. They send those who register a fever to a nearby isolation area for rapid assessments for possible COVID-19 infection and, if warranted, referral to a hospital for treatment.

“These are simple, inexpensive facilities that can save lives, no matter where they are used,” concludes Abdou.